Look Again at This Image of St. Boniface. What Indicates That He Is a Saint?

| Saint Boniface | |

|---|---|

Saint Boniface past Cornelis Bloemaert, c. 1630 | |

| Bishop Apostle to the Germans | |

| Built-in | c. 675 [one] Crediton, Dumnonia |

| Died | v June 754 (aged around 79) most Dokkum, Francia |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Eastern Orthodox Church Anglican Communion Lutheranism |

| Major shrine | Fulda Cathedral, St Boniface Catholic Church, Crediton, Great britain |

| Feast | 5 June |

| Attributes | In bishop'due south robes, volume pierced by a sword (too axe; oak; scourge) |

| Patronage | Fulda; Germania; England (Orthodox Church building; jointly with Ss. Augustine of Canterbury, and Cuthbert of Lindisfarne. The Orthodox Church too recognises him as patron Saint of Federal republic of germany); Devon |

Boniface (Latin: Bonifatius; c. 675[2] – 5 June 754), built-in in Crediton in Anglo-Saxon England, was a leading figure in the Anglo-Saxon mission to the Germanic parts of the Frankish Empire during the 8th century. He organised significant foundations of the church in Germany and was made archbishop of Mainz past Pope Gregory Iii. He was martyred in Frisia in 754, along with 52 others, and his remains were returned to Fulda, where they remainder in a sarcophagus which has become a site of pilgrimage. Boniface's life and decease every bit well every bit his piece of work became widely known, there being a wealth of material available—a number of vitae, particularly the near-gimmicky Vita Bonifatii auctore Willibaldi, legal documents, possibly some sermons, and above all his correspondence. He is venerated as a saint in the Christian church and became the patron saint of Germania, known as the "Apostle to the Germans".

Norman F. Cantor notes the three roles Boniface played that made him "one of the truly outstanding creators of the first Europe, as the apostle of Germania, the reformer of the Frankish church, and the principal fomentor of the alliance between the papacy and the Carolingian family."[3] Through his efforts to reorganize and regulate the church of the Franks, he helped shape the Latin Church in Europe, and many of the dioceses he proposed remain today. Afterward his martyrdom, he was quickly hailed as a saint in Fulda and other areas in Germania and in England. He is still venerated strongly today past German language Catholics. Boniface is celebrated as a missionary; he is regarded every bit a unifier of Europe, and he is regarded by German Catholics every bit a national figure. In 2022 Devon County Council with the back up of the Anglican and Cosmic churches in Exeter and Plymouth, officially recognised St Boniface as the Patron Saint of Devon.

Early life and first mission to Frisia [edit]

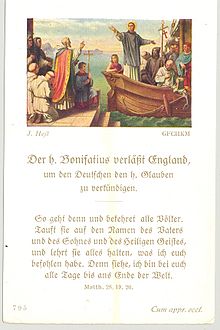

Prayer card, early 20th century, depicting Boniface leaving England

The primeval Bonifacian vita, Willibald's, does not mention his identify of nativity but says that at an early historic period he attended a monastery ruled by Abbot Wulfhard in escancastre,[4] or Examchester,[5] which seems to denote Exeter, and may have been one of many monasteriola congenital by local landowners and churchmen; nothing else is known of it outside the Bonifacian vitae.[6] This monastery is believed to have occupied the site of the Church of St Mary Major in the City of Exeter, demolished in 1971, next to which was later built Exeter Cathedral.[7] Later tradition places his birth at Crediton, but the earliest mention of Crediton in connection to Boniface is from the early fourteenth century,[8] in John Grandisson'south Legenda Sanctorum: The Proper Lessons for Saints' Days according to the use of Exeter.[ix] In 1 of his letters Boniface mentions he was "born and reared...[in] the synod of London",[ten] just he may have been speaking metaphorically.[11]

According to the vitae, Winfrid was of a respected and prosperous family. Against his father'south wishes he devoted himself at an early on age to the monastic life. He received further theological training in the Benedictine monastery and minster of Nhutscelle (Nursling),[12] not far from Winchester, which nether the management of abbot Winbert had grown into an industrious heart of learning in the tradition of Aldhelm.[13] Winfrid taught in the abbey school and at the age of thirty became a priest; in this time, he wrote a Latin grammer, the Ars Grammatica, besides a treatise on verse and some Aldhelm-inspired riddles.[14] While picayune is known about Nursling outside of Boniface'southward vitae, it seems clear that the library there was significant. To supply Boniface with the materials he needed, information technology would have contained works by Donatus, Priscian, Isidore, and many others.[fifteen] Around 716, when his abbot Wynberth of Nursling died, he was invited (or expected) to assume his position—it is possible that they were related, and the practise of hereditary correct among the early Anglo-Saxons would affirm this.[16] Winfrid, however, declined the position and in 716 set out on a missionary expedition to Frisia.

Early missionary work in Frisia and Germania [edit]

Boniface first left for the continent in 716. He traveled to Utrecht, where Willibrord, the "Apostle to the Frisians," had been working since the 690s. He spent a year with Willibrord, preaching in the countryside, but their efforts were frustrated past the war then being carried on betwixt Charles Martel and Radbod, King of the Frisians. Willibrord fled to the abbey he had founded in Echternach (in modern-twenty-four hours Luxembourg) while Boniface returned to Nursling.

Boniface returned to the continent the adjacent yr and went straight to Rome, where Pope Gregory 2 renamed him "Boniface", after the (legendary) quaternary-century martyr Boniface of Tarsus, and appointed him missionary bishop for Germania—he became a bishop without a diocese for an expanse that lacked any church building organization. He would never return to England, though he remained in correspondence with his countrymen and kinfolk throughout his life.

According to the vitae Boniface felled the Donar Oak, Latinized by Willibald as "Jupiter'south oak," near the present-mean solar day town of Fritzlar in northern Hesse. According to his early biographer Willibald, Boniface started to chop the oak downwardly, when all of a sudden a cracking wind, as if by phenomenon, blew the ancient oak over. When the gods did non strike him down, the people were amazed and converted to Christianity. He built a chapel dedicated to Saint Peter from its woods at the site[17]—the chapel was the get-go of the monastery in Fritzlar. This account from the vita is stylized to portray Boniface as a singular graphic symbol who lonely acts to root out paganism. Lutz von Padberg and others point out that what the vitae leave out is that the activity was most likely well-prepared and widely publicized in accelerate for maximum effect, and that Boniface had footling reason to fear for his personal safety since the Frankish fortified settlement of Büraburg was nearby.[18] According to Willibald, Boniface later had a church with an attached monastery built in Fritzlar,[xix] on the site of the previously built chapel, according to tradition.[xx]

Boniface and the Carolingians [edit]

Fulda Sacramentary, Saint Boniface baptizing (elevation) and existence martyred (bottom)

The support of the Frankish mayors of the palace (maior domos), and later the early Pippinid and Carolingian rulers, was essential for Boniface's work. Boniface had been under the protection of Charles Martel from 723 onwards.[21] The Christian Frankish leaders desired to defeat their rival power, the pagan Saxons, and to incorporate the Saxon lands into their own growing empire. Boniface's campaign of destruction of ethnic Germanic pagan sites may have benefited the Franks in their campaign against the Saxons.

In 732, Boniface traveled once again to Rome to written report, and Pope Gregory III conferred upon him the pallium as archbishop with jurisdiction over what is now Germany. Boniface once again set out for the German lands and continued his mission, but too used his authority to work on the relations between the papacy and the Frankish church. Rome wanted more control over that church building, which information technology felt was much too independent and which, in the eyes of Boniface, was subject to worldly corruption. Charles Martel, after having defeated the forces of the Umayyad Caliphate during the Battle of Tours (732), had rewarded many churches and monasteries with lands, but typically his supporters who held church offices were allowed to do good from those possessions. Boniface would take to wait until the 740s earlier he could try to address this situation, in which Frankish church officials were essentially sinecures, and the church itself paid little listen to Rome. During his third visit to Rome in 737–38, he was made papal legate for Federal republic of germany.[22]

Later Boniface's 3rd trip to Rome, Charles Martel established iv dioceses in Bavaria (Salzburg, Regensburg, Freising, and Passau) and gave them to Boniface as archbishop and metropolitan over all Frg east of the Rhine. In 745, he was granted Mainz as metropolitan come across.[23] In 742, 1 of his disciples, Sturm (also known as Sturmi, or Sturmius), founded the abbey of Fulda not far from Boniface's earlier missionary outpost at Fritzlar. Although Sturm was the founding abbot of Fulda, Boniface was very involved in the foundation. The initial grant for the abbey was signed by Carloman, the son of Charles Martel, and a supporter of Boniface'due south reform efforts in the Frankish church building. Boniface himself explained to his old friend, Daniel of Winchester, that without the protection of Charles Martel he could "neither administer his church, defend his clergy, nor forbid idolatry".

According to German historian Gunther Wolf, the loftier bespeak of Boniface'south career was the Concilium Germanicum, organized by Carloman in an unknown location in April 743. Although Boniface was not able to safeguard the church from property seizures past the local dignity, he did accomplish one goal, the adoption of stricter guidelines for the Frankish clergy,[24] who frequently hailed directly from the nobility. After Carloman'due south resignation in 747 he maintained a sometimes turbulent relationship with the king of the Franks, Pepin; the claim that he would accept crowned Pepin at Soissons in 751 is at present generally discredited.[25]

Boniface balanced this support and attempted to maintain some independence, notwithstanding, past attaining the support of the papacy and of the Agilolfing rulers of Bavaria. In Frankish, Hessian, and Thuringian territory, he established the dioceses of Würzburg and Erfurt. By appointing his own followers as bishops, he was able to retain some independence from the Carolingians, who most likely were content to give him leeway as long every bit Christianity was imposed on the Saxons and other Germanic tribes.

Last mission to Frisia [edit]

Saint Boniface catacomb, Fulda

Nailhole in the Ragyndrudis Codex

According to the vitae, Boniface had never relinquished his promise of converting the Frisians, and in 754 he fix out with a retinue for Frisia. He baptized a great number and summoned a general meeting for confirmation at a identify non far from Dokkum, between Franeker and Groningen. Instead of his converts, however, a group of armed robbers appeared who slew the aged archbishop. The vitae mention that Boniface persuaded his (armed) comrades to lay downward their arms: "Stop fighting. Lay downward your arms, for nosotros are told in Scripture not to return evil for evil but to overcome evil by good."[26]

Having killed Boniface and his company, the Frisian bandits ransacked their possessions simply found that the company'southward luggage did not contain the riches they had hoped for: "they broke open the chests containing the books and institute, to their dismay, that they held manuscripts instead of gilt vessels, pages of sacred texts instead of silver plates."[27] They attempted to destroy these books, the earliest vita already says, and this business relationship underlies the status of the Ragyndrudis Codex, at present held as a Bonifacian relic in Fulda, and supposedly i of 3 books found on the field by the Christians who inspected it afterward. Of those three books, the Ragyndrudis Codex shows incisions that could have been fabricated by sword or axe; its story appears confirmed in the Utrecht hagiography, the Vita altera, which reports that an eye-witness saw that the saint at the moment of death held up a gospel as spiritual protection.[28] The story was later repeated by Otloh'southward vita; at that time, the Ragyndrudis Codex seems to take been firmly continued to the martyrdom.

Boniface'due south remains were moved from the Frisian countryside to Utrecht, and then to Mainz, where sources contradict each other regarding the beliefs of Lullus, Boniface's successor as archbishop of Mainz. Co-ordinate to Willibald'south vita Lullus allowed the body to be moved to Fulda, while the (later) Vita Sturmi, a hagiography of Sturm past Eigil of Fulda, Lullus attempted to block the move and proceed the body in Mainz.[29]

His remains were somewhen cached in the abbey church of Fulda later on resting for some time in Utrecht, and they are entombed within a shrine below the loftier altar of Fulda Cathedral, previously the abbey church. There is good reason to believe that the Gospel he held up was the Codex Sangallensis 56, which shows damage to the upper margin, which has been cut back equally a class of repair.

Veneration [edit]

Fulda [edit]

Veneration of Boniface in Fulda began immediately after his decease; his grave was equipped with a decorative tomb effectually ten years later his burial, and the grave and relics became the center of the abbey. Fulda monks prayed for newly elected abbots at the grave site before greeting them, and every Monday the saint was remembered in prayer, the monks prostrating themselves and reciting Psalm 50. After the abbey church building was rebuilt to become the Ratgar Basilica (dedicated 791), Boniface's remains were translated to a new grave: since the church had been enlarged, his grave, originally in the west, was now in the middle; his relics were moved to a new apse in 819. From then on Boniface, as patron of the abbey, was regarded every bit both spiritual intercessor for the monks and legal owner of the abbey and its possessions, and all donations to the abbey were done in his name. He was honored on the appointment of his martyrdom, v June (with a mass written past Alcuin), and (around the twelvemonth 1000) with a mass dedicated to his appointment as bishop, on ane December.[30]

Dokkum [edit]

Willibald's vita describes how a visitor on horseback came to the site of the martyrdom, and a hoof of his equus caballus got stuck in the mire. When it was pulled loose, a well sprang upward. By the time of the Vita altera Bonifatii (ninth century), there was a church building on the site, and the well had become a "fountain of sweet water" used to sanctify people. The Vita Liudgeri, a hagiographical business relationship of the work of Ludger, describes how Ludger himself had built the church, sharing duties with two other priests. According to James Palmer, the well was of great importance since the saint's torso was hundreds of miles away; the physicality of the well allowed for an ongoing connection with the saint. In addition, Boniface signified Dokkum's and Frisia's "connect[ion] to the rest of (Frankish) Christendom".[31]

Memorials [edit]

Saint Boniface memorial in Fritzlar, Frg

Statue of St. Boniface at the Mainz Cathedral

Saint Boniface's banquet day is celebrated on 5 June in the Roman Catholic Church building, the Lutheran Church, the Anglican Communion and the Eastern Orthodox Church building.

A famous statue of Saint Boniface stands on the grounds of Mainz Cathedral, seat of the archbishop of Mainz. A more modern rendition stands facing St. Peter'due south Church of Fritzlar.

The UK National Shrine is located at the Catholic church at Crediton, Devon, which has a bas-relief of the felling of Thor's Oak, past sculptor Kenneth Carter. The sculpture was unveiled past Princess Margaret in his native Crediton, located in Newcombes Meadow Park. There is also a series of paintings there by Timothy Moore. There are quite a few churches dedicated to St. Boniface in the Britain: Bunbury, Cheshire; Chandler's Ford and Southampton Hampshire; Adler Street, London; Papa Westray, Orkney; St Budeaux, Plymouth (now demolished); Bonchurch, Isle of Wight; Cullompton, Devon.

Bishop George Errington founded St Boniface's Cosmic Higher, Plymouth in 1856. The school celebrates Saint Boniface on five June each year.

In 1818, Father Norbert Provencher founded a mission on the east banking concern of the Red River in what was and then Rupert's Land, building a log church and naming information technology subsequently St. Boniface. The log church was consecrated equally Saint Boniface Cathedral after Provencher was himself consecrated as a bishop and the diocese was formed. The customs that grew effectually the cathedral somewhen became the metropolis of Saint Boniface, which merged into the metropolis of Winnipeg in 1971. In 1844, four Gray Nuns arrived by canoe in Manitoba, and in 1871, built Western Canada's starting time hospital: St. Boniface Infirmary, where the Assiniboine and Red Rivers run into. Today, St. Boniface is regarded as Winnipeg's main French-speaking district and the center of the Franco-Manitobain community, and St. Boniface Infirmary is the second-largest hospital in Manitoba.

Boniface (Wynfrith) of Crediton is remembered in the Church of England with a Lesser Festival on i June.[32]

[edit]

Some traditions credit Saint Boniface with the invention of the Christmas tree. The vitae mention nothing of the sort. Nonetheless, it is mentioned on a BBC-Devon website, in an business relationship which places Geismar in Bavaria,[33] and in a number of educational books, including St. Boniface and the Little Fir Tree,[34] The Brightest Star of All: Christmas Stories for the Family,[35] The American normal readers,[36] and a short story past Henry van Dyke, "The First Christmas Tree".[37]

Sources and writings [edit]

Saint Boniface statue in Fulda, Germany

Vitae [edit]

The earliest "Life" of Boniface was written by a certain Willibald, an Anglo-Saxon priest who came to Mainz afterward Boniface'south death,[38] around 765. Willibald'due south biography was widely dispersed; Levison lists some forty manuscripts.[39] According to his lemma, a grouping of iv manuscripts including Codex Monacensis 1086 are copies directly from the original.[xl]

Listed 2d in Levison's edition is the entry from a late ninth-century Fulda document: Boniface's status every bit a martyr is attested past his inclusion in the Fulda Martyrology which also lists, for instance, the appointment (1 November) of his translation in 819, when the Fulda Cathedral had been rebuilt.[41] A Vita Bonifacii was written in Fulda in the ninth century, possibly by Candidus of Fulda, but is now lost.[42]

The next vita, chronologically, is the Vita altera Bonifatii auctore Radbodo, which originates in the Bishopric of Utrecht, and was probably revised by Radboud of Utrecht (899–917). Mainly agreeing with Willibald, it adds an eye-witness who presumably saw the martyrdom at Dokkum. The Vita tertia Bonifatii likewise originates in Utrecht. It is dated between 917 (Radboud's death) and 1075, the twelvemonth Adam of Bremen wrote his Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum, which used the Vita tertia.[43] [44]

A later vita, written by Otloh of St. Emmeram (1062–1066), is based on Willibald's and a number of other vitae as well as the correspondence, and also includes data from local traditions.

Correspondence [edit]

Boniface engaged in regular correspondence with fellow churchmen all over Western Europe, including the three popes he worked with, and with some of his kinsmen back in England. Many of these letters contain questions about church reform and liturgical or doctrinal matters. In well-nigh cases, what remains is one half of the chat, either the question or the reply. The correspondence as a whole gives evidence of Boniface'due south widespread connections; some of the messages also testify an intimate human relationship especially with female correspondents.[45]

There are 150 messages in what is generally called the Bonifatian correspondence, though not all them are by Boniface or addressed to him. They were assembled by order of archbishop Lullus, Boniface's successor in Mainz, and were initially organized into two parts, a department containing the papal correspondence and some other with his individual messages. They were reorganized in the eighth century, in a roughly chronological ordering. Otloh of St. Emmeram, who worked on a new vita of Boniface in the eleventh century, is credited with compiling the complete correspondence as nosotros accept it.[45] Much of this correspondence comprises the commencement part of the Vienna Boniface Codex, also known equally Codex Vindobonensis 751.

The correspondence was edited and published already in the seventeenth century, by Nicolaus Serarius.[46] Stephan Alexander Würdtwein's 1789 edition, Epistolae S. Bonifacii Archiepiscopi Magontini, was the ground for a number of (fractional) translations in the nineteenth century. The beginning version to be published by Monumenta Germaniae Historica (MGH) was the edition by Ernst Dümmler (1892); the most administrative version until today is Michael Tangl'due south 1912 Die Briefe des Heiligen Bonifatius, Nach der Ausgabe in den Monumenta Germaniae Historica, published by MGH in 1916.[45] This edition is the basis of Ephraim Emerton'south selection and translation in English language, The Messages of Saint Boniface, start published in New York in 1940; it was republished virtually recently with a new introduction by Thomas F.X. Noble in 2000.

Included among his letters and dated to 716 is one to Abbess Edburga of Minster-in-Thanet containing the Vision of the Monk of Wenlock.[47] This otherworld vision describes how a violently ill monk is freed from his body and guided by angels to a place of judgment, where angels and devils fight over his soul every bit his sins and virtues come alive to charge and defend him. He sees a hell of purgation full of pits vomiting flames. There is a bridge over a pitch-black boiling river. Souls either fall from it or safely attain the other side cleansed of their sins. This monk fifty-fifty sees some of his contemporary monks and is told to warn them to repent before they dice. This vision bears signs of influence by the Apocalypse of Paul, the visions from the Dialogues of Gregory the Great, and the visions recorded by Bede.[48]

Sermons [edit]

Some fifteen preserved sermons are traditionally associated with Boniface, but that they were actually his is not generally accepted.

Grammar and verse [edit]

Early in his career, before he left for the continent, Boniface wrote the Ars Bonifacii, a grammatical treatise presumably for his students in Nursling. Helmut Gneuss reports that i manuscript copy of the treatise originates from (the south of) England, mid-eighth century; information technology is now held in Marburg, in the Hessisches Staatsarchiv.[49] He also wrote a treatise on verse, the Caesurae uersuum, and a drove of xx acrostic riddles, the Enigmata, influenced greatly by Aldhelm and containing many references to works of Vergil (the Aeneid, the Georgics, and the Eclogues).[50] The riddles fall into two sequences of ten poems. The outset, De virtutibus ('on the virtues'), comprises: one. de ueritate/truth; 2. de fide catholica/the Catholic religion; 3. de spe/hope; four. de misericordia/compassion; five. de caritate/love; half dozen. de iustitia/justice; 7. de patientia/patience; 8. de pace uera, cristiana/true, Christian peace; 9. de humilitate cristiania/Christian humility; ten. de uirginitate/virginity. The second sequence, De vitiis ('on the vices'), comprises: 1. de neglegentia/carelessness; 2. de iracundia/hot temper; iii. de cupiditate/greed; 4. de superbia/pride; 5. de crapula/intemperance; 6. de ebrietate/drunkenness; 7. de luxoria/fornication; 8. de inuidia/envy; nine. de ignorantia/ignorance; ten. de uana gloria/vainglory.[51]

3 octosyllabic poems written in clearly Aldhelmian fashion (co-ordinate to Andy Orchard) are preserved in his correspondence, all composed before he left for the continent.[52]

Boosted materials [edit]

A letter of the alphabet by Boniface charging Aldebert and Clement with heresy is preserved in the records of the Roman Council of 745 that condemned the 2.[53] Boniface had an interest in the Irish gaelic canon law collection known equally Collectio canonum Hibernensis, and a late 8th/early 9th-century manuscript in Würzburg contains, besides a selection from the Hibernensis, a list of rubrics that mention the heresies of Clemens and Aldebert. The relevant folios containing these rubrics were well-nigh likely copied in Mainz, Würzburg, or Fulda—all places associated with Boniface.[53] Michael Glatthaar suggested that the rubrics should be seen as Boniface'south contribution to the agenda for a synod.[54]

Anniversary and other celebrations [edit]

Boniface's decease (and birth) has given ascension to a number of noteworthy celebrations. The dates for some of these celebrations have undergone some changes: in 1805, 1855, and 1905 (and in England in 1955) anniversaries were calculated with Boniface's decease dated in 755, co-ordinate to the "Mainz tradition"; in Mainz, Michael Tangl's dating of the martyrdom in 754 was not accepted until after 1955. Celebrations in Federal republic of germany centered on Fulda and Mainz, in the Netherlands on Dokkum and Utrecht, and in England on Crediton and Exeter.

Celebrations in Frg: 1805, 1855, 1905 [edit]

Medal minted for the Boniface anniversary in Fulda, 1905

The first German celebration on a fairly large scale was held in 1805 (the ane,050th anniversary of his death), followed by a similar celebration in a number of towns in 1855; both of these were predominantly Catholic diplomacy emphasizing the role of Boniface in German language history. But if the celebrations were mostly Catholic, in the first part of the 19th century the respect for Boniface in full general was an ecumenical thing, with both Protestants and Catholics praising Boniface as a founder of the German nation, in response to the German nationalism that arose after the Napoleonic era came to an end. The 2d part of the 19th century saw increased tension between Catholics and Protestants; for the latter, Martin Luther had become the model German, the founder of the modern nation, and he and Boniface were in direct competition for the honor.[55] In 1905, when strife between Catholic and Protestant factions had eased (one Protestant church published a celebratory pamphlet, Gerhard Ficker's Bonifatius, der "Apostel der Deutschen"), in that location were small-scale celebrations and a publication for the occasion on historical aspects of Boniface and his piece of work, the 1905 Festgabe by Gregor Richter and Carl Scherer. In all, the content of these early on celebrations showed evidence of the continuing question well-nigh the meaning of Boniface for Frg, though the importance of Boniface in cities associated with him was without question.[56]

1954 celebrations [edit]

In 1954, celebrations were widespread in England, Germany, and holland, and a number of these celebrations were international affairs. Especially in Germany, these celebrations had a distinctly political annotation to them and often stressed Boniface equally a kind of founder of Europe, such as when Konrad Adenauer, the (Catholic) German chancellor, addressed a oversupply of 60,000 in Fulda, celebrating the feast day of the saint in a European context: "Das, was wir in Europa gemeinsam haben, [ist] gemeinsamen Ursprungs" ("What we accept in common in Europe comes from the same source").[57]

1980 papal visit [edit]

When Pope John Paul 2 visited Germany in Nov 1980, he spent two days in Fulda (17 and 18 November). He celebrated Mass in Fulda Cathedral with 30,000 gathered on the foursquare in forepart of the edifice, and met with the German Bishops' Conference (held in Fulda since 1867). The pope adjacent celebrated mass outside the cathedral, in front end of an estimated crowd of 100,000, and hailed the importance of Boniface for High german Christianity: "Der heilige Bonifatius, Bischof und Märtyrer, bedeutet den 'Anfang' des Evangeliums und der Kirche in Eurem State" ("The holy Boniface, bishop and martyr, signifies the start of the gospel and the church in your country").[58] A photograph of the pope praying at Boniface's grave became the centerpiece of a prayer card distributed from the cathedral.

2004 celebrations [edit]

In 2004, anniversary celebrations were held throughout Northwestern Germany and Utrecht, and Fulda and Mainz—generating a dandy amount of academic and popular interest. The event occasioned a number of scholarly studies, esp. biographies (for instance, by Auke Jelsma in Dutch, Lutz von Padberg in German, and Klaas Bruinsma in Western frisian), and a fictional completion of the Boniface correspondence (Lutterbach, Mit Axt und Evangelium).[59] A German musical proved a great commercial success,[lx] and in holland an opera was staged.[61]

Scholarship on Boniface [edit]

In that location is an extensive torso of literature on the saint and his work. At the time of the various anniversaries, edited collections were published containing essays by some of the best-known scholars of the time, such every bit the 1954 drove Sankt Bonifatius: Gedenkgabe zum Zwölfhundertsten Todestag [62] and the 2004 collection Bonifatius—Vom Angelsächsischen Missionar zum Apostel der Deutschen.[63] In the mod era, Lutz von Padberg published a number of biographies and articles on the saint focusing on his missionary praxis and his relics. The most administrative biography remains Theodor Schieffer'due south Winfrid-Bonifatius und dice Christliche Grundlegung Europas (1954).[64] [65]

See likewise [edit]

- List of Cosmic saints

- Religion in Germany

- Saint Boniface, patron saint archive

- St Boniface's Cosmic Higher, Plymouth, England

References [edit]

Notes [edit]

- ^ Boniface, Saint. Vol. iii (15th ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1974. pp. 31–32. ISBN0-85229-305-4.

- ^ Aherne, Consuelo Maria. "Saint Boniface". Britannica . Retrieved twenty September 2016.

- ^ Cantor 167-68.

- ^ Levison half-dozen.

- ^ Talbot 28.

- ^ Schieffer 76–77; 103–105.

- ^ "St Mary Major – Cathedral Thousand, Exeter Memories website, 2015".

- ^ Orme 97; Hockey 106.

- ^ Levison xxix.

- ^ Emerton 81.

- ^ Flechner 47.

- ^ Levison nine.

- ^ Schieffer 105–106.

- ^ Gneuss 38.

- ^ Gneuss 37–40.

- ^ Yorke.

- ^ Levison 31–32.

- ^ von Padberg 40–41.

- ^ Levison 35.

- ^ Rau 494 north.10.

- ^ Greenaway 25.

- ^ Moore.

- ^ Good.

- ^ Wolf 2–v.

- ^ Wolf 5.

- ^ Talbot 56.

- ^ Talbot 57.

- ^ Schieffer 272-73.

- ^ Palmer 158.

- ^ Kehl, "Entstehung und Verbreitung" 128-32.

- ^ Palmer 162.

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England . Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ "Devon Myths and Legends."

- ^ Melmoth, Jenny and Val Hayward (1999). St. Boniface and the Trivial Fir Tree: A Story to Color. Warrington: Alfresco Books. ISBN 1-873727-15-1.

- ^ Papa, Carrie (2008). The Brightest Star of All: Christmas Stories for the Family unit. Abingdon Printing. ISBN 978-0-687-64813-ix.

- ^ Harvey, May Louise (1912). The American normal readers: fifth volume: "How Saint Boniface Kept Christmas Eve." 207-22. Silver, Burdett and Co.

- ^ Dyke, Henry van. "The Outset Christmas Tree". Retrieved xxx December 2011.

- ^ This is not the Willibald who was appointed by Boniface every bit Bishop of Eichstatt: "The writer of the Life was a simple priest who had never come into direct contact with Boniface and what he says is based upon the facts that he was able to collect from those who had been Boniface's disciples." Talbot 24.

- ^ Levison xvii–xxvi.

- ^ Levison xxxviii.

- ^ Levison xlvii.

- ^ Becht-Jördens, Gereon (1991). "Neue Hinweise zum Rechtsstatus des Klosters Fulda aus der Vita Aegil des Brun Candidus". Hessisches Jahrbuch für Landesgeschichte (in German). 41: 11–29.

- ^ Levison lvi–lviii.

- ^ Haarländer.

- ^ a b c Noble xxxiv–xxxv.

- ^ Epistolae s. Bonifacii martyris, primi moguntini archiepiscopi, published in 1605 in Mainz and republished in 1625, and once again in 1639, Paris.

- ^ Emerton, 25–31; Tangl, 7–15.

- ^ Eileen Gardiner, Medieval Visions of Heaven and Hell: A Sourcebook (New York: Garland, 9113, 143–45).

- ^ Gneuss 130, particular 849.

- ^ Lapidge 38.

- ^ 'Aenigmata Bonifatii', ed. by Fr. Glorie, trans. by Karl J. Minst, in Tatuini omnia opera, Variae collectiones aenigmatum merovingicae aetatis, Anonymus de dubiis nominibus, Corpus christianorum: serial latina, 133-133a, 2 vols (Turnholt: Brepols, 1968), I 273-343.

- ^ Orchard 62–63.

- ^ a b Meeder, Sven (2011). "Boniface and the Irish Heresy of Clemens". Church History. 80 (2): 251–80. doi:10.1017/S0009640711000035.

- ^ Glatthaar 134-63.

- ^ Weichlein, Siegfried (2004). "Bonifatius als politischer Heiliger im 19. und xx. Jahrhundert". In Imhof, Michael; Stasch, Gregor Chiliad. (eds.). Bonifatius: Vom angelsächsischen Missionar zum Apostel der Deutschen (in German). Petersberg: Michael Imhof Verlag. pp. 219–34.

- ^ Nichtweiß 283-88.

- ^ Pralle 59.

- ^ Grave 134.

- ^ Aaij.

- ^ Hartl.

- ^ Henk Alkema (music) and Peter te Nuyl (libretto). Bonifacius. Leewarden, 2004.

- ^ Ed. Cuno Raabe et al., Fulda: Parzeller, 1954.

- ^ Eds. Michael Imhof and Gregor Stasch, Petersberg: Michael Imhof, 2004.

- ^ Lehmann 193: "In dem auch heute noch als Standardwerk anerkannten Buch Winfrid-Bonifatius und die christlichen Grundlegung Europas von Theodor Schieffer..."

- ^ Mostert, Marco. "Bonifatius als geschiedsvervalser". Madoc. 9 (3): 213–21.

...een nog steeds niet achterhaalde biografie

Bibliography [edit]

- Aaij, Michel (June 2005). "Continental Business: Boniface biographies". The Heroic Historic period. 8 . Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- Cantor, Norman F. (1994). The civilization of the Middle Ages: a completely revised and expanded edition of Medieval history, the life and death of a culture . HarperCollins. p. 168. ISBN978-0-06-092553-vi.

- "Devon Myths and Legends". BBC. eighteen Dec 2007. Retrieved xiv December 2010.

- Emerton, Ephraim (1976). The Letters of Saint Boniface. Columbia University Records of Culture. New York: Norton. ISBN0393091473.

- Ficker, Gerhard (1905). Bonifatius, der "Apostel der Deutschen": Ein Gedenkblatt zum Jubiläumsjahr 1905. Leipzig: Evangelischen Bundes.

- Glatthaar, Michael (2004). Bonifatius und das Sakrileg: zur politischen Dimension eines Rechtsbegriffs. Lang. ISBN9783631533093.

- Greenaway, George William (1955). Saint Boniface: Three Biographical Studies for the Twelfth Centenary Festival. London.

- Flechner, Roy (2013). "St Boniface as historian: a continental perspective on the system of the early Anglo-Saxon church". Anglo-Saxon England. 41: 41–62. doi:10.1017/S0263675112000063. ISSN 0263-6751.

- Van der Goot, Annelies (2005). De moord op Bonifatius: Het spoor terug. Amsterdam: Rubinstein. ISBNxc-5444-877-6.

- Gneuss, Helmut (2001). Handlist of Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts: A List of Manuscripts and Manuscript Fragments Written or Owned in England upward to 1100. Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies. Vol. 241. Tempe: Arizona Middle for Medieval and Renaissance Studies.

- Good, Leanne (2020). "Boniface in Bavaria". In Aaij, Michel; Godlove, Shannon (eds.). A Companion to Boniface. Leiden: Brill.

- Grave, Werner (1980). "Gemeinsam Zeugnis geben": Johannes Paul II. in Deutschland. Butzon & Bercker. p. 134. ISBN3-7666-9144-9.

- Haarländer, Stephanie (2007). "Welcher Bonifatius soll es sein? Bemerkungen zu den Vitae Bonifatii". In Franz J. Felten; Jörg Jarnut; Lutz von Padberg (eds.). Bonifatius—Leben und Nachwirken. Selbstverlag der Gesellschaft für mittelrheinische Kirchengeschichte. pp. 353–61. ISBN978-3-929135-56-5.

- Hartl, Iris (26 March 2009). "Bestätigt: Bonifatius kommt wieder". Fuldaer Zeitung . Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- Frederick, Hockey (1980). "St Boniface in his Correspondence". In H. Farmer, David Hugh (ed.). Benedict's Disciples. Leominster. pp. 105–117.

- Kehl, Petra (1993). Kult und Nachleben des heiligen Bonifatius im Mittelalter (754–1200). Quellen und Abhandlungen zur Geschichte der Abtei und der Diözese Fulda. Vol. 26. Fulda: Parzeller. ISBN9783790002263.

- Kehl, Petra (2004). "Entstehung und Verbreitung des Bonifatiuskultes". In Imhof, Michael; Stasch, Gregor K. (eds.). Bonifatius: Vom Angelsäschsischen Missionar zum Apostel der Deutschen. Petersberg: Michael Imhof. pp. 127–50. ISBN3937251324.

- Lehmann, Karl (2007). "'Geht hinaus in alle Welt...': Zum historischen Erbe und zur Gegenwartsbedeutung des hl. Bonifatius". In Franz J. Felten; Jörg Jarnut; Lutz E. von Padberg (eds.). Bonifatius: Leben und Nachwirken. Gesellschaft für mittelrheinische Kirchengeschichte. pp. 193–210. ISBN978-3-929135-56-five.

- Levison, Wilhelm (1905). Vitae Sancti Bonifati Archiepiscopi Moguntini. Hahn. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- Moore, Michael E. (2020). "Boniface in Francia". In Aaij, Michel; Godlove, Shannon (eds.). A Companion to Boniface. Leiden: Brill.

- Mostert, Marco (1999). 754: Bonifatius bij Dokkum Vermoord. Hilversum: Verloren.

- Nichtweiß, Barbara (2005). "Zur Bonifatius-Verehrung in Mainz im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert". In Barbara Nichtweiß (ed.). Bonifatius in Mainz: Neues Jahrbuch für das Bistum Mainz, Beiträge zur Zeit- und Kulturgeschichte der Diozöse Jg. 2005. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern. pp. 277–92. ISBN3-934450-xviii-0.

- Noble, Thomas F.X.; Ephraim Emerton (2000). The Letters of Saint Boniface. Columbia Upward. ISBN978-0-231-12093-vii . Retrieved xv Dec 2010.

- Orchard, Andy (1994). The Poetic Fine art of Aldhelm. Cambridge Up. ISBN9780521450904.

- Orme, Nicholas (1980). "The Church in Crediton from Saint Boniface to the Reformation". In Timothy Reuter (ed.). The Greatest Englishman: Essays on Boniface and the Church at Crediton. Paternoster. pp. 97–131. ISBN978-0-85364-277-0.

- Padberg, Lutz E. von (2003). Bonifatius: Missionar und Reformer. Beck. ISBN978-3-406-48019-5.

- Palmer, James T. (2009). Anglo-Saxons in a Frankish World (690–900). Studies in the Early Middle Ages. Turnhout: Brepols. ISBN9782503519111.

- Pralle, Ludwig (1954). Gaude Fulda! Das Bonifatiusjahr 1954. Parzeller.

- Rau, Reinhold (1968). Briefe des Bonifatius; Willibalds Leben des Bonifatius. Ausgewählte quellen zur deutschen Geschichte des Mittelalters. Vol. IVb. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Richter, Gregor; Carl Scherer (1905). Festgabe zum Bonifatius-Jubiläum 1905. Fulda: Actiendruckerei.

- "St. Boniface", entry from online version of the Catholic Encyclopedia, 1913 edition.

- Schieffer, Theodor (1972) [1954]. Winfrid-Bonifatius und dice christliche Grundlegung Europas. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN3-534-06065-2.

- Talbot, C. H., ed. The Anglo-Saxon Missionaries in Frg: Beingness the Lives of Southward.S. Willibrord, Boniface, Strum, Leoba and Lebuin, together with the Hodoeporicon of St. Willibald and a Selection from the Correspondence of St. Boniface. New York: Sheed and Ward, 1954.

- The Bonifacian vita was republished in Noble, Thomas F. X. and Thomas Head, eds. Soldiers of Christ: Saints and Saints' Lives in Late Artifact and the Early Middle Ages. University Park: Pennsylvania State Upward, 1995. 109–twoscore.

- Tangl, Michael (1903). "Zum Todesjahr des hl. Bonifatius". Zeitschrift des Vereins für Hessische Geschichte und Landeskunde. 37: 223–50.

- Wolf, Gunther G. (1999). "Dice Peripetie in des Bonifatius Wirksamkeit und die Resignation Karlmanns d.Ä.". Archiv für Diplomatik. 45: 1–5.

- Yorke, Barbara (2007). "The Insular Groundwork to Boniface's Continental Career". In Franz J. Felten; Jörg Jarnut; Lutz von Padberg (eds.). Bonifatius—Leben und Nachwirken. Selbstverlag der Gesellschaft für mittelrheinische Kirchengeschichte. pp. 23–37. ISBN978-3-929135-56-v.

External links [edit]

- "St. Boniface, Archbishop of Mentz, Campaigner of Germany and Martyr", Butler's Lives of the Saints

- Wilhelm Levison, Vitae Sancti Bonifatii

robinsonatephy1951.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Boniface

0 Response to "Look Again at This Image of St. Boniface. What Indicates That He Is a Saint?"

Postar um comentário